In Helen Lee’s captivating sculptures, light speaks.

“No, what's your real name?”

Helen Lee was chatting with her taxi driver, a man from Ethiopia, when he asked the question. He’d sensed something the two of them shared, a custom in immigrant families – as she puts it, “You have an American name, and then another name.” Her Chinese name, which means a red cloud before a snowfall, has no direct translation in English. “It’s like a private identity,” says Lee, who later spelled the cabbie’s query in a necklace.

Lee has lived much of her life in translation. The daughter of professionals from Taiwan (her father was an electrical engineer, her mother a computer programmer), she was born in New Jersey and grew up bilingual, speaking a hybrid “Chinglish” at home. Her grandmother, who raised her while her parents worked, spoke only Mandarin. When it came to interacting with the outside world or even just watching TV, it was Lee who, from a tender age, helped her grandmother negotiate English-speaking society.

“I spent a lot of time moving between Chinese and English, trying to explain something to my grandmother, or thinking about how she might be thinking about it,” Lee, 39, recalls. In her mind, there existed a zone between those two very different languages and cultures, where connections, both linear and lateral, were made.

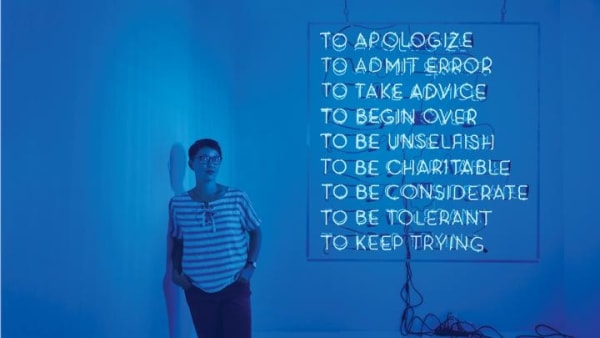

Today, working primarily in glass, Lee draws on that “third space” to make art about language: the emotional power of words, things said and unsaid, and “the weird routes that information takes through translation.” In conversation, ironically, she finds aspects of her work hard to articulate, but her pieces express the ineffable in sublime form, inviting us to consider how we perceive words, gestures, signs, and signals.

“Something about the way glass holds light, to me, resonates with the way that we ask words to hold meaning,” she says. “Glass is this elusive state of matter, visually interesting in that it’s not fixed but fluid, which is how I relate to language.” Light translates her pieces, illuminating their messages. The pieces translate light, revealing information in shadows and reflection.

Text is often present in Lee’s work, sometimes in Verre, a glass-inspired typeface she designed. In Words Are Not Things (2015), shining glass letters spell out the work’s title, prompting us to ponder how something intangible can carry such weight. The glass letters of Placeholder Shelf (2010) cast the shadow of a mysterious phrase, “Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet,” from the gibberish Latin used in print and web design before the actual content is ready; a one-time graphic designer, Lee finds it intriguing that while the sentence is nonsense, “viewers always want to know what it means.” Some pieces don’t incorporate glass but still center on a theme of communication: My Grandmother Held a Pencil Like a Brush (2011) is simply a pencil suspended straight up and down, a nod to Chinese calligraphy technique.

Always fascinated by linguistics, Lee was an avid writer in high school, who “totally identified as a teenage poet.” At 16, her focus shifted when she took a “mind-blowing” summer class in glass. She honored her parents’ wishes to go to MIT, where she majored in architecture, but she spent all her free time in the school’s glass lab. She went on to earn an MFA in glass at Rhode Island School of Design in 2006, then moved to the Bay Area where she worked as a graphic designer while pursuing her studio practice and teaching glass. She married her longtime boyfriend, Matt Bissett, a CNC machinist, in 2012, and the following year was hired to head the glass department at the University of Wisconsin- Madison (the first university studio glass program in America, started by Harvey Littleton in 1962). There, she teaches students “how to use their bodies to influence what happens as material moves from fluid to solid” within a broad creative context she calls “glass and glass-based thinking.”

She takes a careful, considered approach to each work she makes, waiting for concept, material, and process to come together in “the right ratio and proportions of magic.” She chose hot-pink neon for OMG (2015), a rendering in Chinese characters of the Chinese equivalent of “Oh, my God” (which translates literally as “My day!”). For the quiet white floor piece Kowtow (2015), she used a pâte de verre technique to create the effect of a patch of snow. The Chinese custom of bowing deeply to show respect doesn’t really translate into American culture, she observes, whereas “it’s normal for me to go to the graves of my mother or father or grandmother, get down on my hands and knees, and touch my forehead to the ground.” Kowtow captures the sensitivity of the gesture, “so delicate and ginger, like how it feels to hold my body when I’m walking on fresh snow.”

Lately, Lee has found a new well of inspiration in motherhood. For a video announcement of her daughter’s birth two years ago, she sent flashes of mirrored sunlight across a lake using a World War II heliograph she found on eBay. For Maternal Proverb (2015), she inscribed on a large scroll in her own breast milk. She burned the characters with her glassblowing torch to make visible a comment her terminally ill mother had murmured in Chinese while sitting in a hospital waiting room, looking around at the other patients: “Everyone is sick.” In English, the remark sounds flat, not terribly significant. As Lee dissects each Chinese character, an ultra-literal Mandarin translation is much fuller, reading “big family, all together, life sick” – a poignant expression of camaraderie and humanity, reminding us of all that a few words can convey. “It was just something she uttered as she was staring off into space,” says Lee. “And I couldn’t let go of it."

This article originally appeared in the October/November 2017 issue of American Craft.

Copyright © 2017. All rights reserved.

Source: American Craft